How To Build A Product Engineering Culture

How to Build a Product Engineering Culture 🪴A practical handbook about how to run some of your most common product engineering processes.Hey, Luca here, welcome to a weekly edition of Refactoring! To access all our articles, library, and community, subscribe to the paid version: Resources: 🏛️ Library • 💬 Community • 🎙️ Podcast • ❓ About Last week I had a coffee with the CTO of an early stage startup here in Rome. He told me he feels they are not working at their full potential: bottlenecks are everywhere and features go out 1) slowly, and 2) without the level of polish he would like. I know what you are thinking — no CTO is ever happy with these things. But John (not his real name) is an experienced guy. We have known each other for a long time, he has 10+ years of experience in product startups, and his instincts are usually right. So we tried to debug this together. We talked about many things, including, crucially, product engineering — that is, can we remove some bottlenecks and increase velocity by empowering engineers to do more? If you have been following Refactoring or the tech industry at large over the past two years, you know product engineering is a growing trend (or buzzword). When you look at fast moving startups and ask them how they do it, they often mention a combination of: engineers owning features from top to bottom, shipping every day, PMs only doing strategy, and so on. But this is easier said than done. In this utopian world, how should you run the various stages of the SDLC? Who writes requirements? Who does QA? What goes in the backlog and how? What about bugs? There are extremely few companies documenting this journey, explaining exactly how their engineers own more work without compromising quality and while still collaborating well with product, design, or QA. One of these is Atono. Atono is a peculiar company: it’s a small team of industry veterans who are building a software development tool backed by their strong opinions about how software should be made — and they are doing so completely in the open. They maintain a thorough, public handbook about how they work, from principles to internal processes, and a Substack newsletter where they share their learnings about making software, which readily implement in the tool they build. So, this week I sat down with Doug Peete, CPO, and went through some of their best ideas for running a high-performing product team. Here's what we'll cover:

Let's dive in! Disclaimer: I am a fan of what Atono is building and I am grateful to them for partnering on this piece! However, I will only write my unbiased opinion about the practices and tools covered here, Atono included. You can learn more about Atono below 👇 📋 Product managers ≠ backlog managersWhen we say “PMs should not spend most of their time writing specs and grooming backlogs!” we all applaud and nod in agreement, but then who should do it, and how? Without a clear process, you may end up in one of these familiar scenarios:

So, rather than focusing on who does what, start with a few principles about how things should happen: 1) Separate capture from commitment 📥Last week I published a long article about how I take notes. In there, I wrote that one of the biggest improvements in my note-taking process has come from separating the moment where I capture an initial note, to when I refine it and put it in the proper bucket. I even have a dedicated personal ceremony — my weekly review — where I go through all my captured notes and organize them one by one.

I believe the same is true for backlogs. Ideas for new features, improvements, or bug reports, can (and should) come from anywhere: product people, engineers, customer success, sales, or the CEO — and you should be able to capture them properly. This doesn’t mean though, they need to immediately get into the same backlog from which engineers commit on work to be done:

Ideally, you want to trend in a direction where:

But it’s a journey, and it takes time. 2) Keep backlogs radically short 🗳️This journey, however, can only happen if you don’t allow your backlog to balloon. Long backlogs are an anti-pattern for many reasons:

Mary Poppendieck, Agile legend with 30+ years of experience, says “burn your backlog” every time she can, and that you should rather focus on flow:

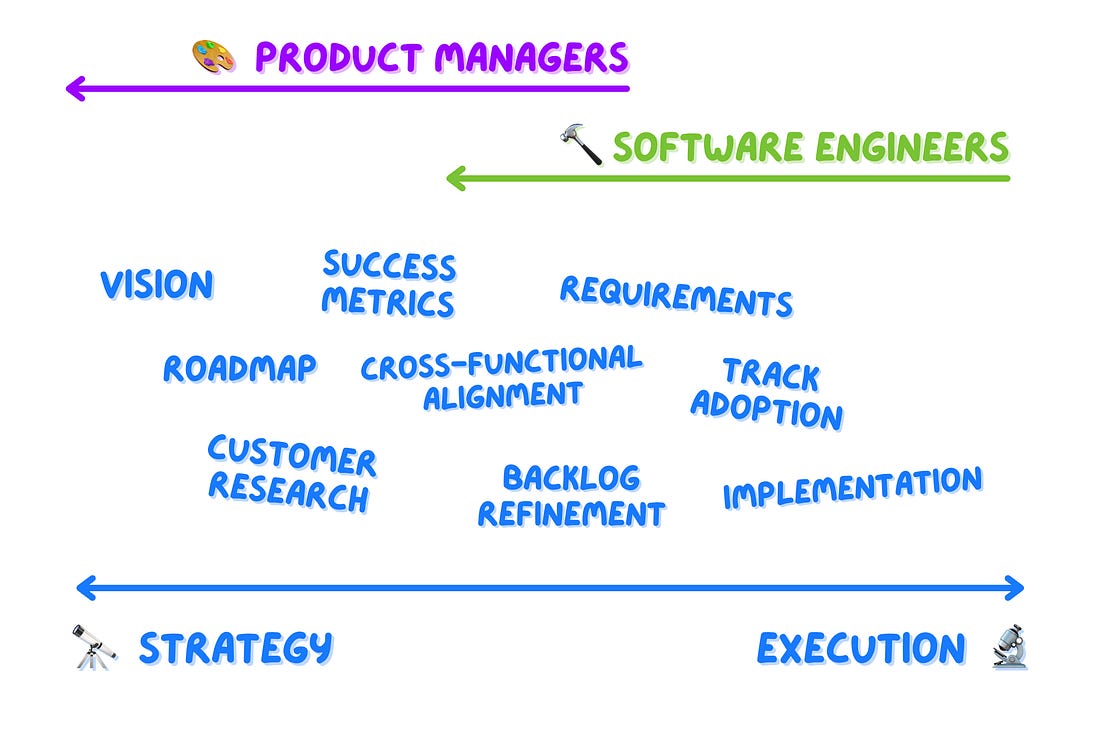

The Atono team only keeps 2-4 weeks of committed work, which means PMs and engineers reject work all the time. Small feature with unclear impact? Reject. Hard to reproduce bug on niche device? Reject. So what should PMs actually do? 🎯The most value PMs can bring is, obviously, through strategic work:

What’s missing? Implementation details. The key idea in product engineering is that engineers own the how, but you have to get there. Engineers get to own the how when they are given the right context about the why; when they have developed, over time, a good product taste; and when they have good building blocks (design and product-wise) that make it easy to make the right choices. Without the above, it’s chaos, and PMs need to stay more hands-on. So how do you get there? Let’s start from an unlikely place: good stories 👇 🎯 User stories are about problems, not solutionsThese days there is a lot of pushback against user stories, as there is against Scrum and many formalisms that we have cargo-culted for decades. Are user stories useful? Well, when I started working as a developer, a lot of our stories looked like this:

As a junior dev, I loved these. Zero ambiguity. I know exactly what to build. Ship it, move on. Now compare it to this other one:... Subscribe to Refactoring to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of Refactoring to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|