How Does Google Docs Work

I wrote this deep dive for paid subscribers. And I'm sending you a preview so you don't miss out. Upgrade your subscription now if you want to read the full article. Also thank you to the 7 people who signed up last week! (If you live in a country with low purchasing power, or you're a student, simply reply to this email to get a discount. Just mention the country name as well.) Unlock access to every deep dive article by becoming a paid subscriber: I spent hours studying how Google Docs works so you don't have to. And I wrote this newsletter to make the key concepts simple and easy for you.

Note: This post is based on my research and may differ from real-world implementation. Once upon a time, there lived a data analyst named Maria. She emailed draft copies many times to different people to prepare monthly reports. So she wasted a ton of time and was frustrated. Until one day, when she decides to use Google Docs for it. Google Docs allows collaborative editing over the internet. It means many users can work on the same document in real-time. Yet it’s difficult to implement Google Docs correctly for 3 reasons:

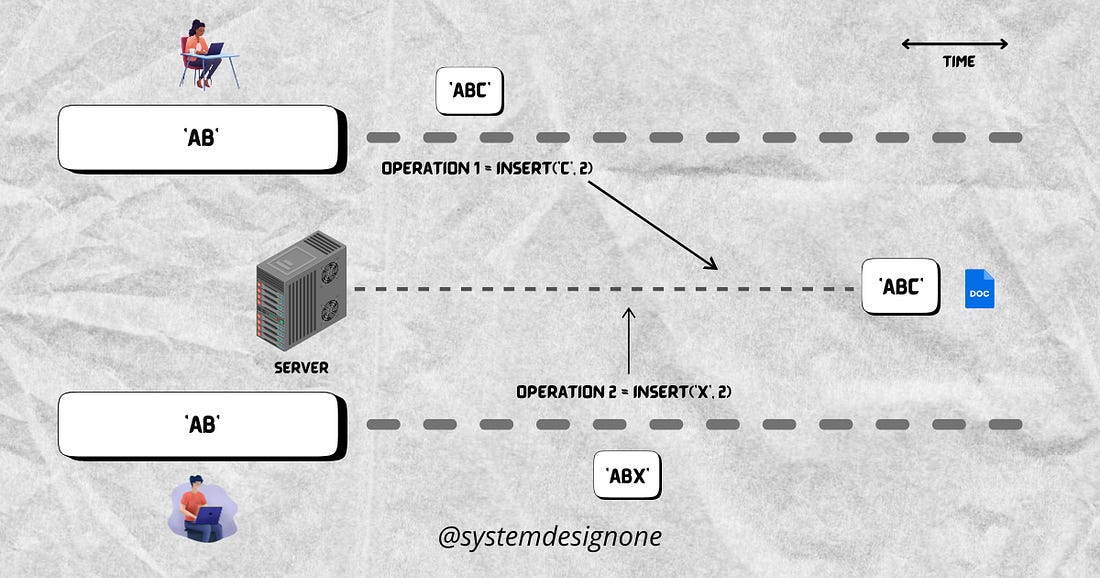

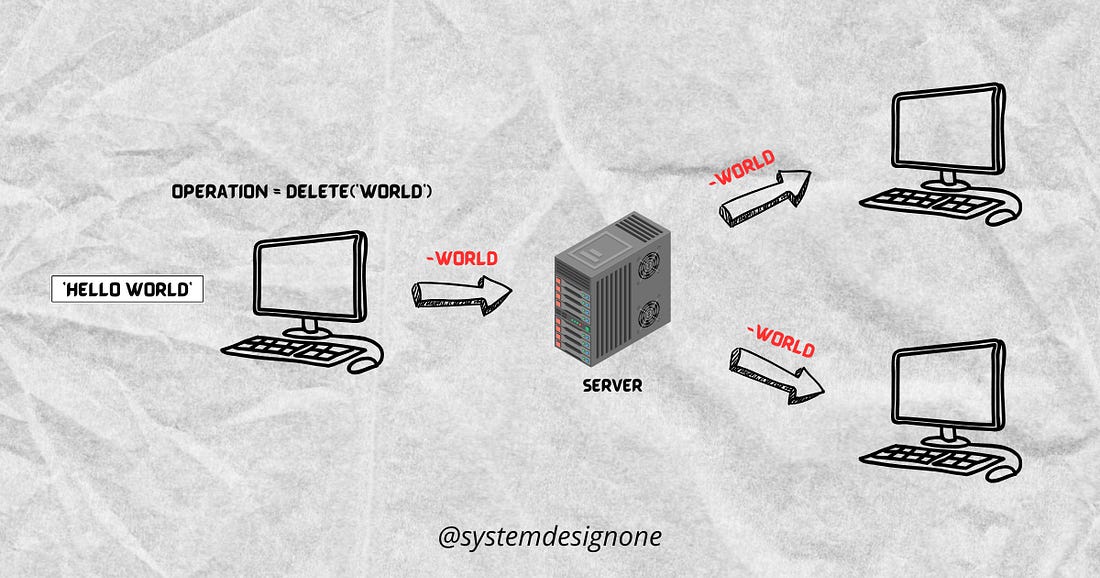

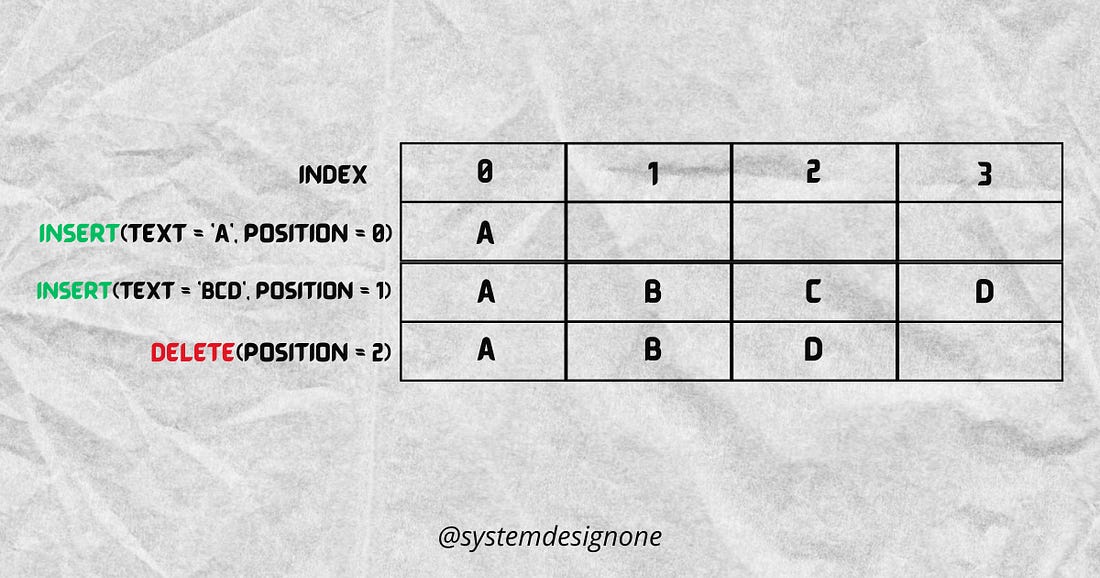

Also a user should be able to make changes while they’re offline. A simple approach to handle concurrency is using pessimistic concurrency control. Pessimistic locking is a mechanism for handling concurrency using a lock. It offers strong consistency, but doesn’t support collaborative editing in real-time. Because it needs a central coordinator to handle data changes, only 1 user can edit at a time. Put simply, only a single document copy is available for write operations at once, while other document copies are read-only. Besides it doesn’t support offline changes. Also a network round-trip across the Earth takes 200 milliseconds. This might cause a poor user experience. So they do latency hiding. The idea is to keep a document copy for each user locally and then run operations locally for high responsiveness. Thus creating the illusion of lower latency than reality. And the system propagates the changes to all users for consistency. A simple approach for latency hiding is using the last-write-wins mechanism. Yet it resolves a conflict without waiting for coordination by applying the most recent update. So there’s a risk of data loss when there are concurrent changes in high-latency networks. It might be a good choice when concurrency is low. But it isn’t suitable for this use case. Onward. An alternative approach to latency hiding is through differential synchronization. It keeps a document copy for each user and tracks the changes locally. The system doesn’t send the entire document when something changes, but only the difference (diff). Yet there’s a performance overhead in sending a diff for every change. Also differential synchronization only tracks diffs, and not the reason behind a change. So conflict resolution might be difficult. While resolving conflicts manually affects the user experience. So Google Docs uses an optimistic concurrency control technique called operational transformation (OT). OT is an algorithm to show document changes without wait times on high-latency networks. It allows different document copies to accept write operations at once. Also it handles conflict resolution automatically without locks or user interventions. Besides OT tolerates divergence among document copies and converges them later. Think of operational transformation as an event-passing mechanism; it ensures each user has the same document state even with unsynchronized changes. With OT, the system saves each change as an event. Put simply, a change doesn’t affect the underlying character of a document; instead, it adds an event to the revision log. The system then displays the document by replaying the revision log from its start. Operational transformation saves a document as a set of operations, but it's complex to implement properly. How Does Google Docs WorkGoogle Docs uses a client-server architecture for simplicity. Here’s how it works:... Subscribe to The System Design Newsletter to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of The System Design Newsletter to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|